Lessons from Building AI Agents for Financial Services

The hard-won technical lessons from building Fintool, an AI agent for Financial Services

I’ve spent the last two years building AI agents for financial services. Along the way, I’ve accumulated a fair number of battle scars and learnings that I want to share.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

- The Sandbox Is Not Optional - Why isolated execution environments are essential for multi-step agent workflows

- Context Is the Product - How we normalize heterogeneous financial data into clean, searchable context

- The Parsing Problem - The hidden complexity of extracting structured data from adversarial SEC filings

- Skills Are Everything - Why markdown-based skills are becoming the product, not the model

- The Model Will Eat Your Scaffolding - Designing for obsolescence as models improve

- The S3-First Architecture - Why S3 beats databases for file storage and user data

- The File System Tools - How ReadFile, WriteFile, and Bash enable complex financial workflows

- Temporal Changed Everything - Reliable long-running tasks with proper cancellation handling

- Real-Time Streaming - Building responsive UX with delta updates and interactive agent workflows

- Evaluation Is Not Optional - Domain-specific evals that catch errors before they cost money

- Production Monitoring - The observability stack that keeps financial agents reliable

Why financial services is extremely hard. This domain doesn’t forgive mistakes. Numbers matter. A wrong revenue figure, a misinterpreted guidance statement, an incorrect DCF assumption. Professional investors make million-dollar decisions based on our output. One mistake on a $100M position and you’ve destroyed trust forever.

The users are also demanding. Professional investors are some of the smartest, most time-pressed people you’ll ever work with. They spot bullshit instantly. They need precision, speed, and depth. You can’t hand-wave your way through a valuation model or gloss over nuances in an earnings call.

This forces me to develop an almost paranoid attention to detail. Every number gets double-checked. Every assumption gets validated. Every model gets stress-tested. You start questioning everything the LLM outputs because you know your users will. A single wrong calculation in a DCF model and you lose credibility forever.

I sometimes feel that the fear of being wrong becomes our best feature.

Over the years building with LLM, we’ve made bold infrastructure bets early and I think we have been right. For instance, when Claude Code launched with its filesystem-first agentic approach, we immediately adopted it. It was not an obvious bet and it was a massive revamp of our architecture. I was extremely lucky to have Thariq from Anthropic Claude Code jumping on a Zoom and opening my eyes to the possibilities.

At the time the whole industry, including Fintool, was all building elaborate RAG pipelines with vector databases and embeddings. After reflecting on the future of information retrieval with agents I wrote “the RAG obituary” and Fintool moved fully to agentic search. We even decided to retire our precious embedding pipeline. Sad but whatever is best for the future!

People thought we were crazy. The article got a lot of praise and a lot of negative comments. Now I feel most startups are adopting these best practices.

I believe we’re early on several other architectural choices too. I’m sharing them here because the best way to test ideas is to put them out there.

Let’s start with the biggest one.

The Sandbox Is Not Optional

When we first started building Fintool in 2023, I thought sandboxing might be overkill. “We’re just running Python scripts” I told myself. “What could go wrong?”

Haha. Everything. Everything could go wrong.

The first time an LLM decided to `rm -rf /` on our server (it was trying to “clean up temporary files”), I became a true believer.

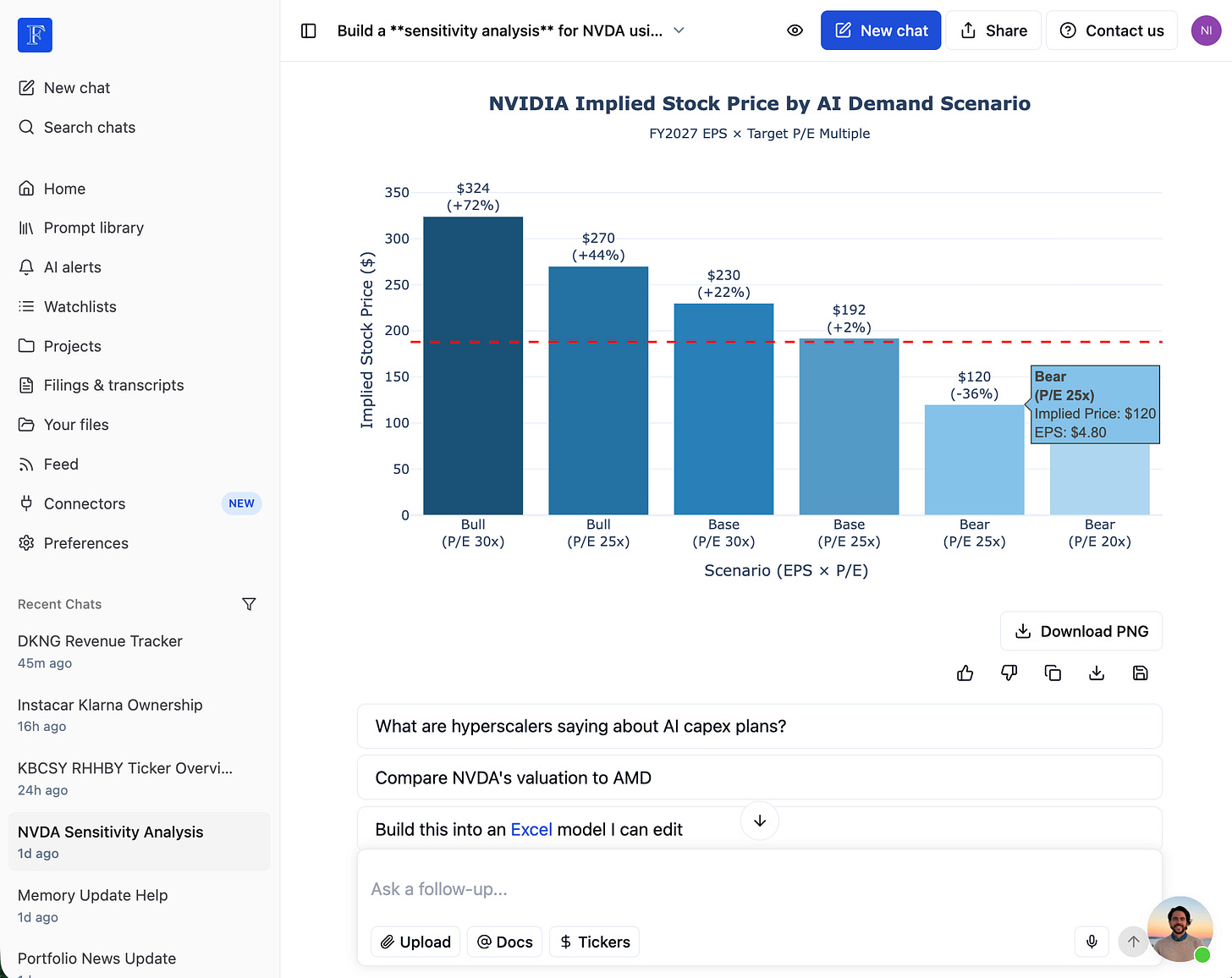

Here’s the thing: agents need to run multi-step operations. A professional investor asks for a DCF valuation and that’s not a single API call. The agent needs to research the company, gather financial data, build a model in Excel, run sensitivity analysis, generate complex charts, iterate on assumptions. That’s dozens of steps, each potentially modifying files, installing packages, running scripts.

You can’t do this without code execution. And executing arbitrary code on your servers is insane. Every chat application needs a sandbox.

Today each user gets their own isolated environment. The agent can do whatever it wants in there. Delete everything? Fine. Install weird packages? Go ahead. It’s your sandbox, knock yourself out.

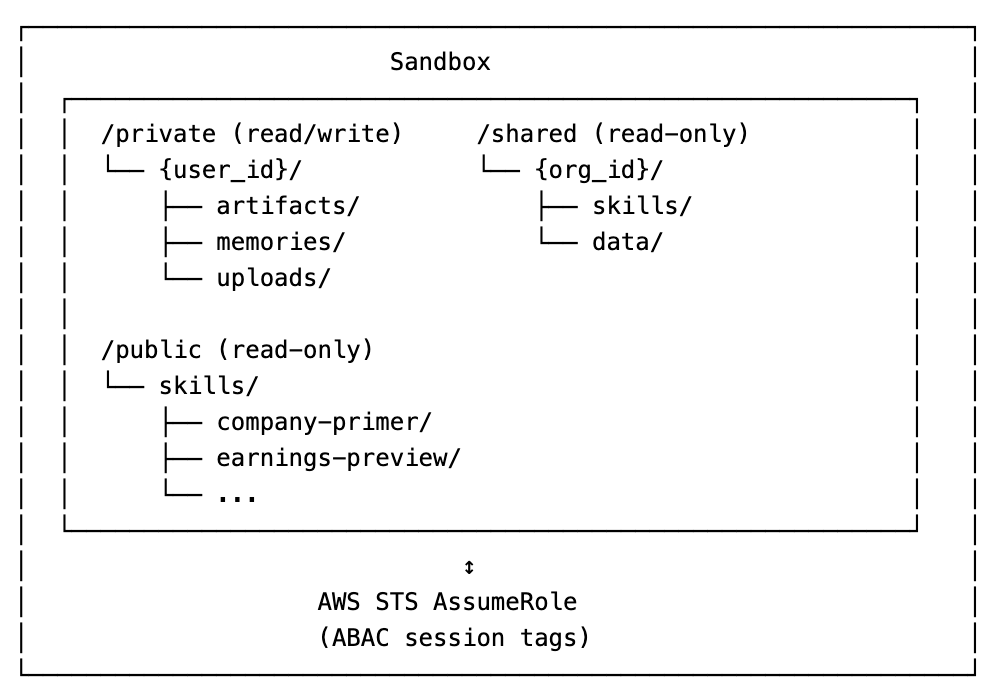

The architecture looks like this:

Three mount points. Private is read/write for your stuff. Shared is read-only for your organization. Public is read-only for everyone.

The magic is in the credentials. We use AWS ABAC (Attribute-Based Access Control) to generate short-lived credentials scoped to specific S3 prefixes.

User A literally cannot access User B’s data. The IAM policy uses `${aws:PrincipalTag/S3Prefix}` to restrict access. The credentials physically won’t allow it. This is also very good for Enterprise deployment.

We also do sandbox pre-warming. When a user starts typing, we spin up their sandbox in the background.

By the time they hit enter, the sandbox is ready. 600 second timeout, extended by 10 minutes on each tool usage. The sandbox stays warm across conversation turns.

So sandboxes are amazing but the under-discussed magic of sandboxes is the support for the filesystem. Which brings us to the next lesson learned about context.

Context Is the Product

Your agent is only as good as the context it can access. The real work isn’t prompt engineering it’s turning messy financial data from dozens of sources into clean, structured context the model can actually use. This requires a massive domain expertise from the engineering team.

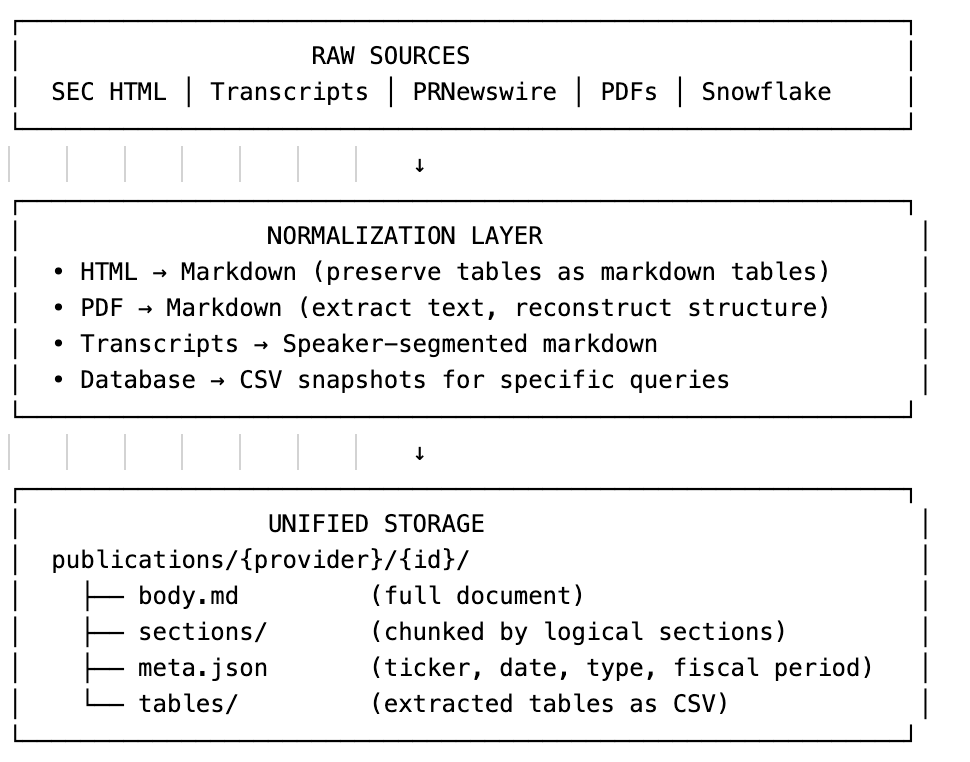

The heterogeneity problem. Financial data comes in every format imaginable:

- SEC filings: HTML with nested tables, exhibits, signatures

- Earnings transcripts: Speaker-segmented text with Q&A sections

- Press releases: Semi-structured HTML from PRNewswire

- Research reports: PDFs with charts and footnotes

- Market data: Snowflake/databases with structured numerical data

- News: Articles with varying quality and structure

- Alternative data: Satellite imagery, web traffic, credit card panels

- Broker research: Proprietary PDFs with price targets and models

- Fund filings: 13F holdings, proxy statements, activist letters

Each source has different schemas, different update frequencies, different quality levels.

Agent needs one thing: clean context it can reason over.

The normalization layer. Everything becomes one of three formats:

- Markdown for narrative content (filings, transcripts, articles)

- CSV/tables for structured data (financials, metrics, comparisons)

- JSON metadata for searchability (tickers, dates, document types, fiscal periods)

Chunking strategy matters. Not all documents chunk the same way:

- 10-K filings: Section by regulatory structure (Item 1, 1A, 7, 8...)

- Earnings transcripts: Chunk by speaker turn (CEO remarks, CFO remarks, Q&A by analyst)

- Press releases: Usually small enough to be one chunk

- News articles: Paragraph-level chunks

- 13F filings: By holder and position changes quarter-over-quarter

The chunking strategy determines what context the agent retrieves. Bad chunks = bad answers.

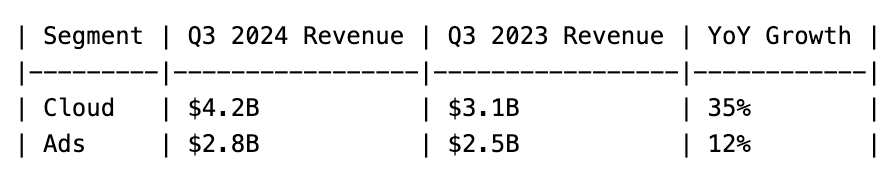

Tables are special. Financial data is full of tables and csv. Revenue breakdowns, segment performance, guidance ranges. LLMs are surprisingly good at reasoning over markdown tables:

But they’re terrible at reasoning over HTML `<table>` tags or raw CSV dumps. The normalization layer converts everything to clean markdown tables.

Metadata enables retrieval. The user asks the agent: “What did Apple say about services revenue in their last earnings call?”

To answer this, Fintool needs:

- Ticker resolution (AAPL → correct company)

- Document type filtering (earnings transcript, not 10-K)

- Temporal filtering (most recent, not 2019)

- Section targeting (CFO remarks or revenue discussion, not legal disclaimers)

This is why `meta.json` exists for every document. Without structured metadata, you’re doing keyword search over a haystack. It speeds up the search, big time!

Anyone can call an LLM API. Not everyone has normalized decades of financial data into searchable, chunked markdown with proper metadata. The data layer is what makes agents actually work.

The Parsing Problem

Normalizing financial data is 80% of the work. Here’s what nobody tells you.

SEC filings are adversarial. They’re not designed for machine reading. They’re designed for legal compliance:

- Tables span multiple pages with repeated headers

- Footnotes reference exhibits that reference other footnotes

- Numbers appear in text, tables, and exhibits—sometimes inconsistently

- XBRL tags exist but are often wrong or incomplete

- Formatting varies wildly between filers (every law firm has their own template)

We tried off-the-shelf PDF/HTML parsers. They failed on:

- Multi-column layouts in proxy statements

- Nested tables in MD&A sections (tables within tables within tables)

- Watermarks and headers bleeding into content

- Scanned exhibits (still common in older filings and attachments)

- Unicode issues (curly quotes, em-dashes, non-breaking spaces)

The Fintool parsing pipeline:

Raw Filing (HTML/PDF)

↓

Document structure detection (headers, sections, exhibits)

↓

Table extraction with cell relationship preservation

↓

Entity extraction (companies, people, dates, dollar amounts)

↓

Cross-reference resolution (Ex. 10.1 → actual exhibit content)

↓

Fiscal period normalization (FY2024 → Oct 2023 to Sep 2024 for Apple)

↓

Quality scoring (confidence per extracted field)

Table extraction deserves its own work. Financial tables are dense with meaning. A revenue breakdown table might have:

- Merged header cells spanning multiple columns

- Footnote markers (1), (2), (a), (b) that reference explanations below

- Parentheses for negative numbers: $(1,234) means -1234

- Mixed units in the same table (millions for revenue, percentages for margins)

- Prior period restatements in italics or with asterisks

We score every extracted table on:

- Cell boundary accuracy (did we split/merge correctly?)

- Header detection (is row 1 actually headers, or is there a title row above?)

- Numeric parsing (is “$1,234” parsed as 1234 or left as text?)

- Unit inference (millions? billions? per share? percentage?)

Tables below 90% confidence get flagged for review. Low-confidence extractions don’t enter the agent’s context—garbage in, garbage out.

Fiscal period normalization is critical. “Q1 2024” is ambiguous:

- Calendar Q1 (January-March 2024)

- Apple’s fiscal Q1 (October-December 2023)

- Microsoft’s fiscal Q1 (July-September 2023)

- “Reported in Q1” (filed in Q1, but covers the prior period)

We maintain a fiscal calendar database for 10,000+ companies. Every date reference gets normalized to absolute date ranges. When the agent retrieves “Apple Q1 2024 revenue,” it knows to look for data from October-December 2023.

This is invisible to users but essential for correctness. Without it, you’re comparing Apple’s October revenue to Microsoft’s January revenue and calling it “same quarter.”

Skills Are Everything

Here’s the thing nobody tells you about building AI agents: the model is not the product. The skills are now the product.

I learned this the hard way. We used to try making the base model “smarter” through prompt engineering. Tweak the system prompt, add examples, write elaborate instructions. It helped a little. But skills were the missing part.

In October 2025, Anthropic formalized this with Agent Skills a specification for extending Claude with modular capability packages. A skill is a folder containing a `SKILL.md` file with YAML frontmatter (name and description), plus any supporting scripts, references, or data files the agent might need.

We’d been building something similar for months before the announcement. The validation felt good but more importantly, having an industry standard means our skills can eventually be portable.

Without skills, models are surprisingly bad at domain tasks. Ask a frontier model to do a DCF valuation. It knows what DCF is. It can explain the theory. But actually executing one? It will miss critical steps, use wrong discount rates for the industry, forget to add back stock-based compensation, skip sensitivity analysis. The output looks plausible but is subtly wrong in ways that matter.

The breakthrough came when we started thinking about skills as first-class citizens. Like part of the product itself.

A skill is a markdown file that tells the agent how to do something specific. Here’s a simplified version of our DCF skill:

```

# dcf

## When to Use

Use this skill for discounted cash flow valuations.

## Instructions

1. Deep dive on the company using Task tool (understand all segments)

2. Identify the company’s industry and load industry-specific guidelines

3. Gather financial data: revenue, margins, CapEx, working capital

4. Build the DCF model in Excel using xlsx skill

5. Calculate WACC using industry benchmarks

6. Run sensitivity analysis on WACC and terminal growth

7. Validate: reconcile base year to actuals, compare to market price

8. Document your view vs market pricing

## Industry Guidelines

- Technology/SaaS: `/public/skills/dcf/guidelines/technology-saas.md`

- Healthcare/Pharma: `/public/skills/dcf/guidelines/healthcare-pharma-biotech.md`

- Financial Services: `/public/skills/dcf/guidelines/financial-services.md`

[... 10+ industries with specific methodologies]

That’s it. A markdown file. No code changes. No production deployment. Just a file that tells the agent what to do.

Skills are better than code. This matters enormously:

1. Non-engineers can create skills. Our analysts write skills. Our customers write skills. A portfolio manager who’s done 500 DCF valuations can encode their methodology in a skill without writing a single line of Python.

2. No deployment needed. Change a skill file and it takes effect immediately. No CI/CD, no code review, no waiting for release cycles. Domain experts can iterate on their own.

3. Readable and auditable. When something goes wrong, you can read the skill and understand exactly what the agent was supposed to do. Try doing that with a 2,000-line Python module.

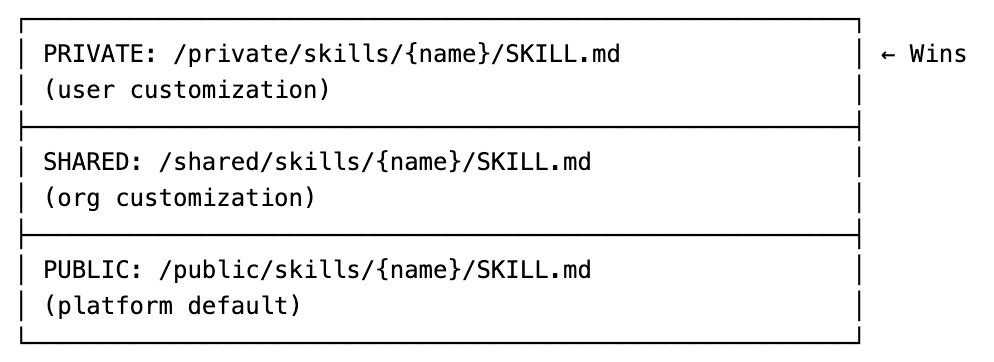

We have a copy-on-write shadowing system: Priority: private > shared > public

So if you don’t like how we do DCF valuations, write your own. Drop it in `/private/skills/dcf/SKILL.md`. Your version wins.

Why we don’t mount all skills to the filesystem. This is important.

The naive approach would be to mount every skill file directly into the sandbox. The agent can just `cat` any skill it needs. Simple, right?

Wrong. Here’s why we use SQL discovery instead:

SELECT user_id, path, metadata

FROM fs_files

WHERE user_id = ANY(:user_ids)

AND path LIKE ‘skills/%/SKILL.md’

1. Lazy loading. We have dozens of skills with extensive documentation like the DCF skill alone has 10+ industry guideline files. Loading all of them into context for every conversation would burn tokens and confuse the model. Instead, we discover skill metadata (name, description) upfront, and only load the full documentation when the agent actually uses that skill.

2. Access control at query time. The SQL query implements our three-tier access model: public skills available to everyone, organization skills for that org’s users, private skills for individual users. The database enforces this. You can’t accidentally expose a customer’s proprietary skill to another customer.

3. Shadowing logic. When a user customizes a skill, their version needs to override the default. SQL makes this trivial—query all three levels, apply priority rules, return the winner. Doing this with filesystem mounts would be a nightmare of symlinks and directory ordering.

4. Metadata-driven filtering. The `fs_files.metadata` column stores parsed YAML frontmatter. We can filter by skill type, check if a skill is main-agent-only, or query any other structured attribute—all without reading the files themselves.

The pattern: S3 is the source of truth, a Lambda function syncs changes to PostgreSQL for fast queries, and the agent gets exactly what it needs when it needs it.

Skills are essential. I cannot emphasize this enough. If you’re building an AI agent and you don’t have a skills system, you’re going to have a bad time. My biggest argument for skills is that top models (Claude or GPT) are post-trained on using Skills. The model wants to fetch skills.

Models just want to learn and what they want to learn is our skills... Until they ate it.

The Model Will Eat Your Scaffolding

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: everything I just told you about skills? It’s temporary in my opinion.

Models are getting better. Fast. Every few months, there’s a new model that makes half your code obsolete. The elaborate scaffolding you built to handle edge cases? The model just... handles them now.

When we started, we needed detailed skills with step-by-step instructions for some simple tasks. “First do X, then do Y, then check Z.” Now? We can often just say for simple task “do an earnings preview” and the model figures it out (kinda of!)

This creates a weird tension. You need skills today because current models aren’t smart enough. But you should design your skills knowing that future models will need less hand-holding. That’s why I’m bullish on markdown file versus code for model instructions. It’s easier to update and delete.

We send detailed feedback to AI labs. Whenever we build complex scaffolding to work around model limitations, we document exactly what the model struggles with and share it with the lab research team. This helps inform the next generation of models. The goal is to make our own scaffolding obsolete.

My prediction: in two years, most of our basic skills will be one-liners. “Generate a 20 tabs DCF.” That’s it. The model will know what that means.

But here’s the flip side: as basic tasks get commoditized, we’ll push into more complex territory. Multi-step valuations with segment-by-segment analysis. Automated backtesting of investment strategies. Real-time portfolio monitoring with complex triggers. The frontier keeps moving.

So we write skills. We delete them when they become unnecessary. And we build new ones for the harder problems that emerge. And all that are files... in our filesystem.

The S3-First Architecture

Here’s something that surprised me: S3 for files is a better database than a database.

We store user data (watchlists, portfolio, preferences, memories, skills) in S3 as YAML files. S3 is the source of truth. A Lambda function syncs changes to PostgreSQL for fast queries.

Writes → S3 (source of truth)

↓

Lambda trigger

↓

PostgreSQL (fs_files table)

↓

Reads ← Fast queries

Why?

- Durability: S3 has 11 9’s. A database doesn’t.

- Versioning: S3 versioning gives you audit trails for free

- Simplicity: YAML files are human-readable. You can debug with `cat`.

- Cost: S3 is cheap. Database storage is not.

The pattern:

- Writes go to S3 directly

- List queries hit the database (fast)

- Single-item reads go to S3 (freshest data)

The sync architecture. We run two Lambda functions to keep S3 and PostgreSQL in sync:

S3 (file upload/delete)

↓

SNS Topic

↓

fs-sync Lambda → Upsert/delete in fs_files table (real-time)

EventBridge (every 3 hours)

↓

fs-reconcile Lambda → Full S3 vs DB scan, fix discrepancies

Both use upsert with timestamp guards—newer data always wins. The reconcile job catches any events that slipped through (S3 eventual consistency, Lambda cold starts, network blips).

User memories live here too. Every user has a `/private/memories/UserMemories.md` file in S3. It’s just markdown—users can edit it directly in the UI. On every conversation, we load it and inject it as context:

python

org_memories, user_memories = await fetch_memories(safe_user_id, org_id)

conversation_manager.add_backend_message(

UserMessage(content=f”<user-memories>\n{user_memories}\n</user-memories>”)

)

This is surprisingly powerful. Users write things like “I focus on small-cap value stocks” or “Always compare to industry median, not mean” or “My portfolio is concentrated in tech, so flag concentration risk.” The agent sees this on every conversation and adapts accordingly.

No migrations. No schema changes. Just a markdown file that the user controls.

Watchlists work the same way. YAML files in S3, synced to PostgreSQL for fast queries. When a user asks about “my watchlist,” we load the relevant tickers and inject them as context. The agent knows what companies matter to this user.

The filesystem becomes the user’s personal knowledge base. Skills tell the agent how to do things. Memories tell it what the user cares about. Both are just files.

The File System Tools

Agents in financial services need to read and write files. A lot of files. PDFs, spreadsheets, images, code. Here’s how we handle it.

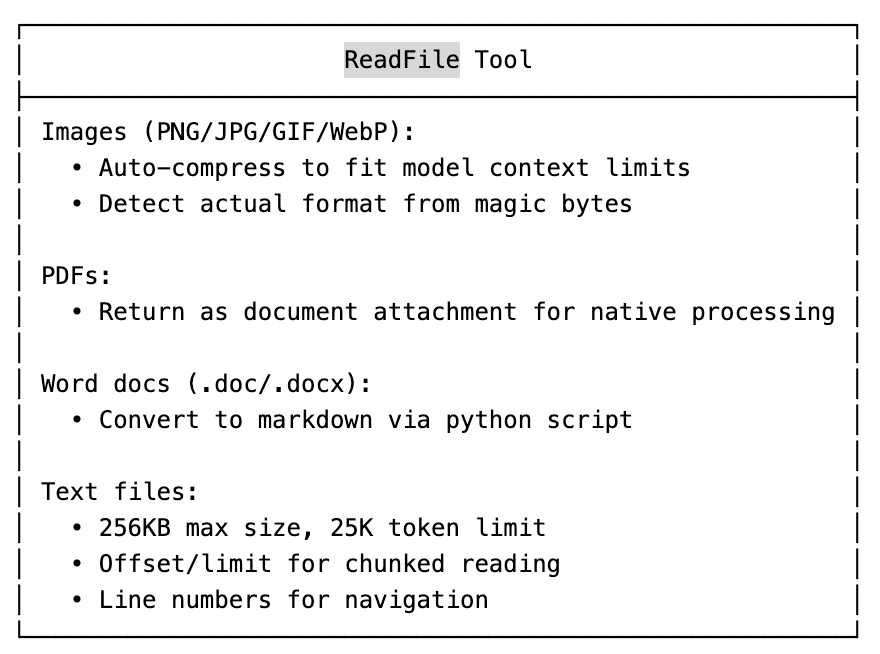

ReadFile handles the complexity:

WriteFile creates artifacts that link back to the UI:

python

# Files in /private/artifacts/ become clickable links

# computer://user_id/artifacts/chart.png → opens in viewer

Bash gives persistent shell access with 180 second timeout and 100K character output limit. Path normalization on everything (LLMs love trying path traversal attacks, it’s hilarious).

Bash is more important than you think. There’s a growing conviction in the AI community that filesystems and bash are the optimal abstraction for AI agents. Braintrust recently ran an eval comparing SQL agents, bash agents, and hybrid approaches for querying semi-structured data.

The results were interesting: pure SQL hit 100% accuracy but missed edge cases. Pure bash was slower and more expensive but caught verification opportunities. The winner? A hybrid approach where the agent uses bash to explore and verify, SQL for structured queries.

This matches our experience. Financial data is messy. You need bash to grep through filing documents, find patterns, explore directory structures. But you also need structured tools for the heavy lifting. The agent needs both—and the judgment to know when to use each.

We’ve leaned hard into giving agents full shell access in the sandbox. It’s not just for running Python scripts. It’s for exploration, verification, and the kind of ad-hoc data manipulation that complex tasks require.

But complex tasks mean long-running agents. And long-running agents break everything.

Temporal Changed Everything

Before Temporal, our long-running tasks were a disaster. User asks for a comprehensive company analysis. That takes 5 minutes. What if the server restarts? What if the user closes the tab and comes back? What if... anything?

We had a homegrown job queue. It was bad. Retries were inconsistent. State management was a nightmare.

Then we switched to Temporal and I wanted to cry tears of joy!

That’s it. Temporal handles worker crashes, retries, everything. If a Heroku dyno restarts mid-conversation (happens all the time lol), Temporal automatically retries on another worker. The user never knows.

The cancellation handling is the tricky part. User clicks “stop,” what happens? The activity is already running on a different server. We use heartbeats sent every few seconds.

We run two worker types:

- Chat workers: User-facing, 25 concurrent activities

- Background workers: Async tasks, 10 concurrent activities

They scale independently. Chat traffic spikes? Scale chat workers.

Next is speed.

Real-Time Streaming

In finance, people are impatient. They’re not going to wait 30 seconds staring at a loading spinner. They need to see something happening.

So we built real-time streaming. The agent works, you see the progress.

Agent → SSE Events → Redis Stream → API → Frontend

The key insight: delta updates, not full state. Instead of sending “here’s the complete response so far” (expensive), we send “append these 50 characters” (cheap).

typescript

enum DeltaOperation {

ADD = “add”, // Insert object at index

APPEND = “append”, // Append to string/array

REPLACE = “replace”,

PATCH = “patch”,

TRUNCATE = “truncate”

}

Streaming rich content with Streamdown. Text streaming is table stakes. The harder problem is streaming rich content: markdown with tables, charts, citations, math equations. We use Streamdown to render markdown as it arrives, with custom plugins for our domain-specific components.

Charts render progressively. Citations link to source documents. Math equations display properly with KaTeX. The user sees a complete, interactive response building in real-time.

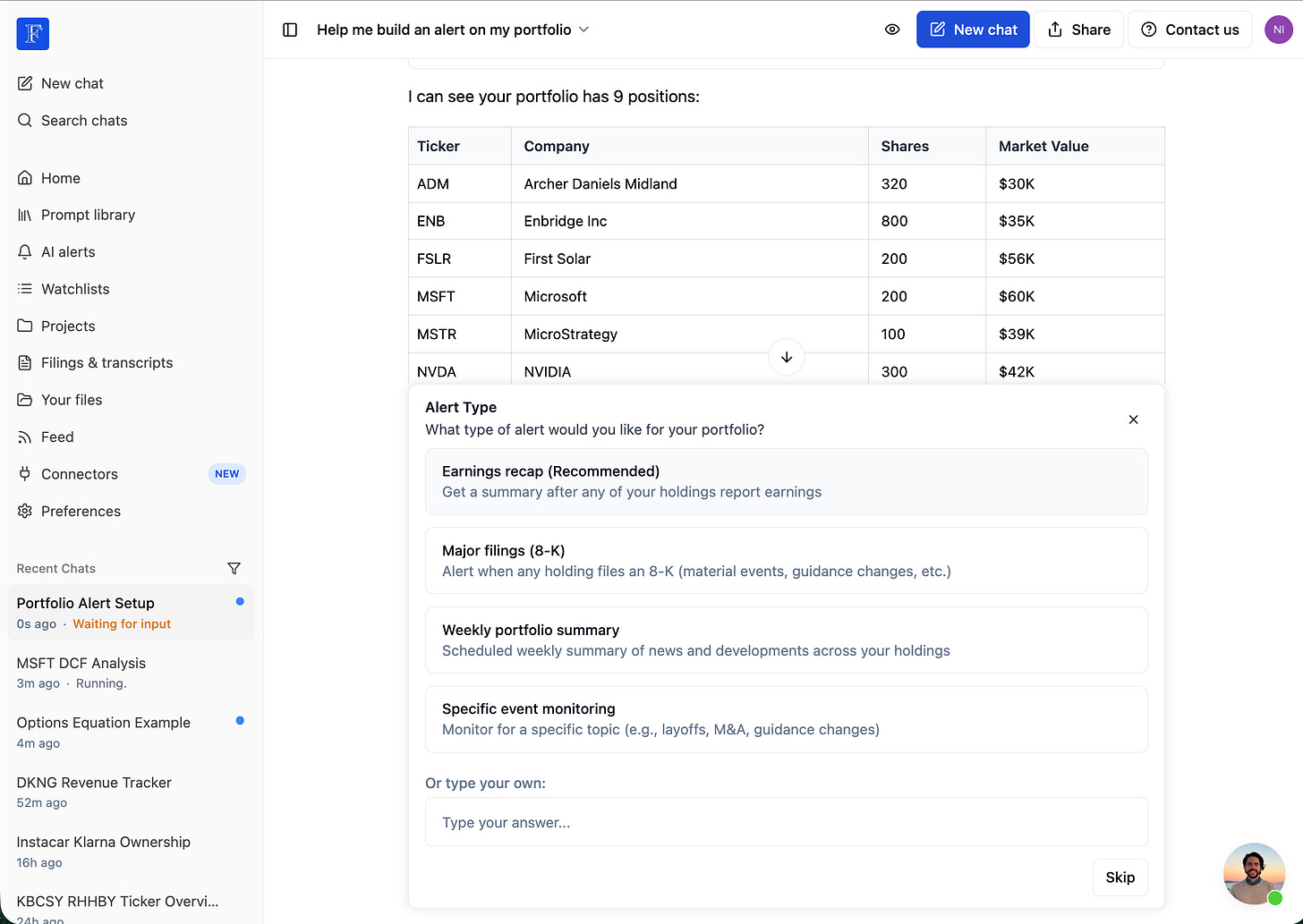

AskUserQuestion: Interactive agent workflows. Sometimes the agent needs user input mid-workflow.

“Which valuation method do you prefer?”

“Should I use consensus estimates or management guidance?”

“Do you want me to include the pipeline assets in the valuation?”

We built an `AskUserQuestion` tool that lets the agent pause, present options, and wai for user input

When the agent calls this tool, the agentic loop intercepts it, saves state, and presents a UI to the user. The user picks an option (or types a custom answer), and the conversation resumes with their choice.

This transforms agents from autonomous black boxes into collaborative tools. The agent does the heavy lifting, but the user stays in control of key decisions. Essential for high-stakes financial work where users need to validate assumptions.

Evaluation Is Not Optional

“Ship fast, fix later” works for most startups. It does not work for financial services.

A wrong earnings number can cost someone money. A misinterpreted guidance statement can lead to bad investment decisions. You can’t just “fix it later” when your users are making million-dollar decisions based on your output.

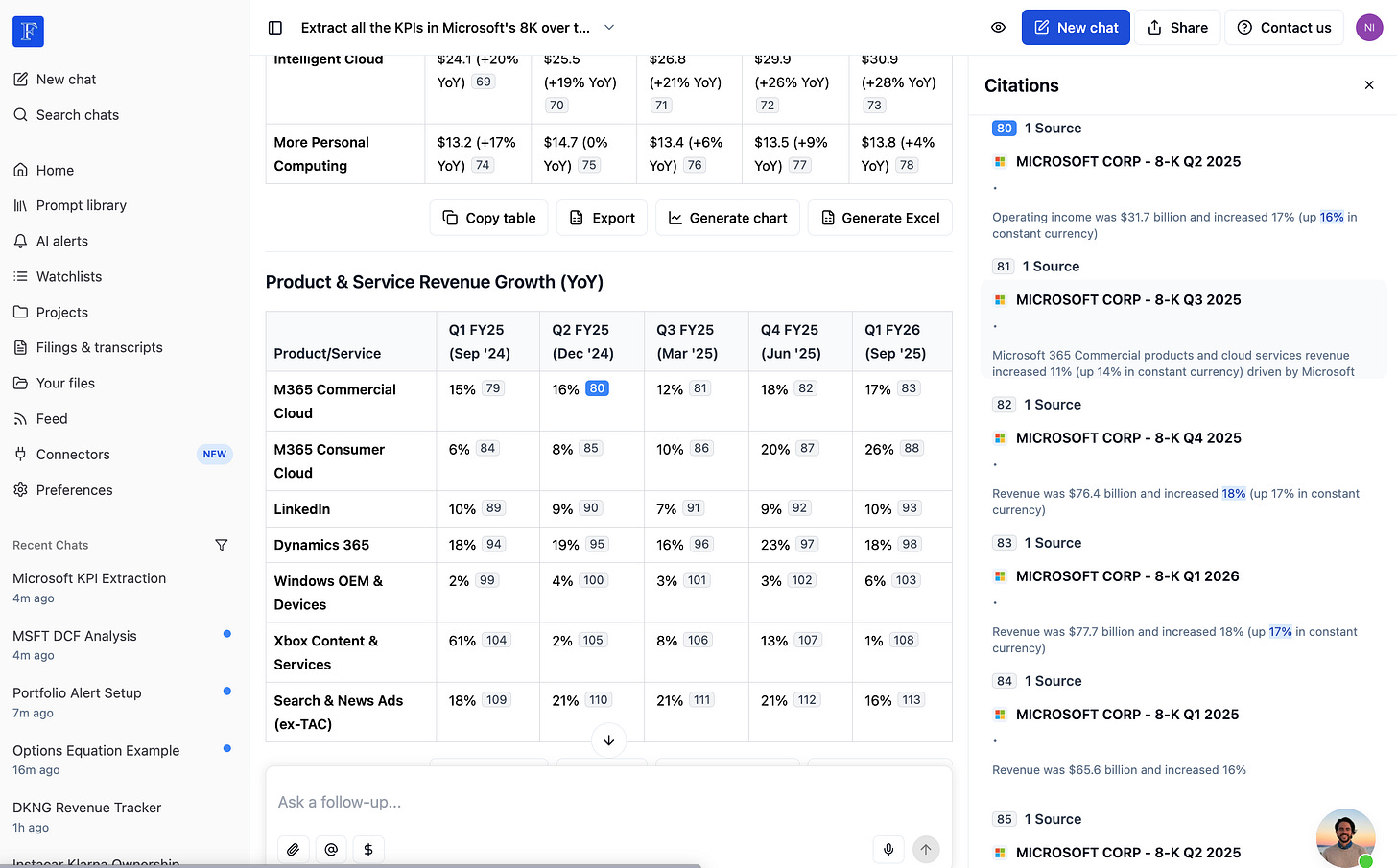

We use Braintrust for experiment tracking. Every model change, every prompt change, every skill change gets evaluated against a test set.

Generic NLP metrics (BLEU, ROUGE) don’t work for finance. A response can be semantically similar but have completely wrong numbers. Building eval datasets is harder than building the agent. We maintain ~2,000 test cases across categories:

Ticker disambiguation. This is deceptively hard:

- “Apple” → AAPL, not APLE (Appel Petroleum)

- “Meta” → META, not MSTR (which some people call “meta”)

- “Delta” → DAL (airline) or is the user talking about delta hedging (options term)?

The really nasty cases are ticker changes. Facebook became META in 2021. Google restructured under GOOG/GOOGL. Twitter became X (but kept the legal entity). When a user asks “What happened to Facebook stock in 2023?”, you need to know that FB → META, and that historical data before Oct 2021 lives under the old ticker.

We maintain a ticker history table and test cases for every major rename in the last decade.

Fiscal period hell. This is where most financial agents silently fail:

- Apple’s Q1 is October-December (fiscal year ends in September)

- Microsoft’s Q2 is October-December (fiscal year ends in June)

- Most companies Q1 is January-March (calendar year)

“Last quarter” on January 15th means:

- Q4 2024 for calendar-year companies

- Q1 2025 for Apple (they just reported)

- Q2 2025 for Microsoft (they’re mid-quarter)

We maintain fiscal calendars for 10,000+ companies. Every period reference gets normalized to absolute date ranges. We have 200+ test cases just for period extraction.

Numeric precision. Revenue of $4.2B vs $4,200M vs $4.2 billion vs “four point two billion.” All equivalent. But “4.2” alone is wrong—missing units. Is it millions? Billions? Per share?

We test unit inference, magnitude normalization, and currency handling. A response that says “revenue was 4.2” without units fails the eval, even if 4.2B is correct.

Adversarial grounding. We inject fake numbers into context and verify the model cites the real source, not the planted one.

Example: We include a fake analyst report stating “Apple revenue was $50B” alongside the real 10-K showing $94B. If the agent cites $50B, it fails. If it cites $94B with proper source attribution, it passes. We have 50 test cases specifically for hallucination resistance.

Eval-driven development. Every skill has a companion eval. The DCF skill has 40 test cases covering WACC edge cases, terminal value sanity checks, and stock-based compensation add-backs (models forget this constantly).

PR blocked if eval score drops >5%. No exceptions.

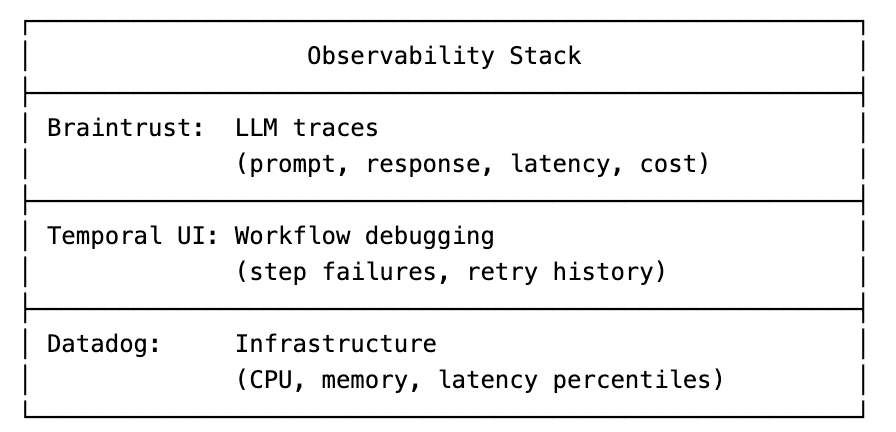

Production Monitoring

Our production setup looks like this:

We auto-file GitHub issues for production errors. Error happens, issue gets created with full context: conversation ID, user info, traceback, links to Braintrust traces and Temporal workflows. Paying customers get `priority:high` label.

Model routing by complexity: simple queries use Haiku (cheap), complex analysis uses Sonnet (expensive). Enterprise users always get the best model.

The Meta Lesson

The biggest lesson isn’t about sandboxes or skills or streaming. It’s this:

The model is not your product. The experience around the model is your product.

Anyone can call Claude or GPT. The API is the same for everyone. What makes your product different is everything else: the data you have access to, the skills you’ve built, the UX you’ve designed, the reliability you’ve engineered and frankly how well you know the industry which is a function of how much time you spend with your customers.

Models will keep getting better. That’s great! It means less scaffolding, less prompt engineering, less complexity. But it also means the model becomes more of a commodity.

Your moat is not the model. Your moat is everything you build around it.

For us, that’s financial data, domain-specific skills, real-time streaming, and the trust we’ve built with professional investors.

What’s yours?

What’s sandbox better to use? Runtime docker is too heavy to process multiple tasks?

This article is superb. Validates my learnings, some intuitions and pushes me forward in ways I've not experienced yet.

I'd like to ask you if you can tell us more about Evals and whether you've been able to get your non tech users to start thinking in terms of evals as well. I've been in the path of advocacy for cross functional teams but it's quite the challenge to target different audiences with a concept like evals (I was avoiding explaining sandboxing/observability to start and focusing on incrementality of intention -> determinism -> stability)